The long running saga of Roger Ng and his former boss at Goldman Sachs, Tim Leissner, and their complicity in the scheme to bilk more than $4 billlion dollars from Malaysia’s sovereign wealth fund under disgraced Prime Minister Najib Razak continues winding its way through federal court in New York, but two things seem pretty clear at this stage: Goldman Sachs definitely participated in this crime, and secondly, there is a significant chance they will get away with it (again).

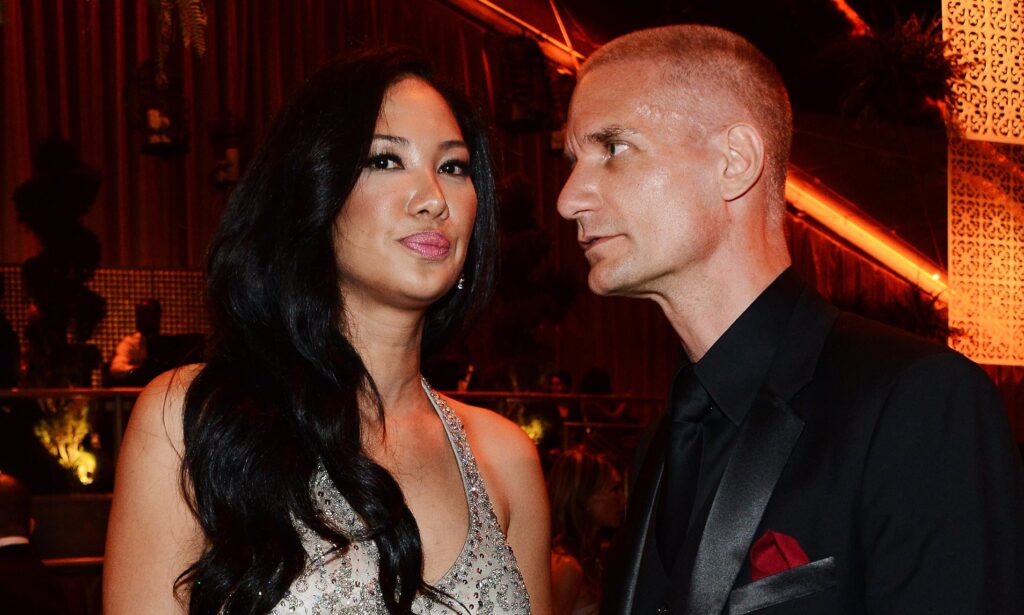

Mr. Leissner acknowledged to the court that he has “lied a lot,” including by presenting a bogus divorce decree to his now-estranged wife, the model and fashion designer Kimora Lee Simmons, so that she would marry him eight years ago. But he insists he’s telling the truth about Mr. Ng, who prosecutors say helped line the pockets of officials in Abu Dhabi and powerful Malaysians close to then Prime Minister Najib Razak.

The looted money from the 1Malaysia Development Berhad, or 1MDB, sovereign wealth fund financed a vast spending spree: paintings by van Gogh and Monet, a yacht that was docked in Bali, a private jet and a clear acrylic grand piano given to a supermodel. It financed a boutique hotel in Beverly Hills, bought a share of the EMI music publishing portfolio and helped make “The Wolf of Wall Street,” the Martin Scorsese movie about Wall Street corruption that netted Leonardo DiCaprio a Golden Globe.

The trial could be the scandal’s final act. Goldman Sachs has paid $5 billion in fines and pleaded guilty on behalf of an Asian subsidiary. Mr. Leissner pleaded guilty and is awaiting sentencing. Mr. Najib, the former prime minister, was convicted in his home country and sentenced to 12 years in jail.

The only other central character of the plot is unlikely to ever face trial: Jho Low, the brash financier accused of being the scheme’s architect, is a fugitive believed to be living in China, beyond the reach of U.S. prosecutors.

Mr. Leissner said Mr. Low was the “decision maker” on all things involving 1MDB but that Mr. Ng was his primary contact at Goldman, which earned roughly $600 million in fees to arrange the $6.5 billion in bond deals for the fund.

“Roger made him one of his clients,” Mr. Leissner said.

He testified that Mr. Ng had set up many of the meetings to plan the scheme, including one at Mr. Low’s London apartment during which Mr. Low drew boxes on a piece of paper with the names of all the officials that would get bribes and gifts. For helping arrange the payments, Mr. Leissner said, he raked in more than $80 million. Prosecutors contend that Mr. Ng’s share was $35 million.

Mr. Ng’s attorneys say that Mr. Leissner has exaggerated and distorted facts to please prosecutors and get a lighter sentence. The money Mr. Ng received, they argue, was to repay a legitimate debt one of Mr. Leissner’s wives owed Mr. Ng’s wife.

“I am set to show this jury he is a liar,” Mr. Ng’s lead lawyer, Marc Agnifilo, told Judge Margo K. Brodie, the chief judge for U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York, during a break in the proceedings. He described Mr. Leissner as “deceptive” and “cunning.”

“There aren’t a lot of guys like him,” Mr. Agnifilo said.

Mr. Leissner’s credibility has been an issue since the investigation began. In a campaign to cast Mr. Leissner as a rogue employee, the bank told regulators and law enforcement officials that he was a master con man who had fooled everyone at the bank.

Rebecca Roiphe, a former prosecutor and a professor at New York Law School who specializes in legal ethics, said it could be tricky to rely on such a witness, but “it isn’t a fatal blow.”

She said a prosecutor can argue that a witness is “a horrible person” and “a serial liar” who has had “a come-to-Jesus moment.”

“That can work when you have really bad people who have lied a lot,” she said.

Mr. Agnifilo got Mr. Leissner to elaborate on how he — not Mr. Ng — oversaw the payment of most of the bribe money. He highlighted Mr. Leissner’s close relationship with Mr. Low by getting Mr. Leissner to confirm his attendance at a star-studded 31st birthday party that Mr. Low arranged for himself in Las Vegas in 2012. (Mr. Leissner said Mr. Ng had also attended, although Mr. Ng was not on the guest list.)

Mr. Agnifilo also had Mr. Leissner recount the many ways he deceived his wives, particularly Ms. Simmons. Mr. Leissner admitted that he had used an email account in the name of his second wife, Judy Chan, to communicate with Ms. Simmons while dating her, and that he was still married to Ms. Chan when he and Ms. Simmons were wed. (Mr. Leissner was also legally married to another woman when he married Ms. Chan.)

And Mr. Agnifilo poked holes in Mr. Leissner’s accounts of details of the 1MDB scheme, particularly the pivotal meeting at Mr. Low’s apartment. He pressed Mr. Leissner on why he told the F.B.I. after his June 2018 arrest that a Morgan Stanley banker had also been present.

Mr. Leissner said he didn’t recall saying that and didn’t know why it would be in an F.B.I. agent’s write-up of the interview. When shown a copy of the F.B.I. report, Mr. Leissner responded: “I don’t know who wrote this or how that report was written.”

Mr. Agnifilo also grilled Mr. Leissner — who was interviewed by law enforcement roughly 50 times before and after his guilty plea in August 2018 — about how he had trickled out details of the meeting. Mr. Leissner had no explanation for why he didn’t mention Mr. Low’s writing down the names of people on a chart until an interview with the F.B.I. in April last year.

When forced to discuss some of his deceptions, Mr. Leissner sounded almost sheepish, including when he testified about using some of the looted money to buy a $10 million house for one of his girlfriends so she would not go to the authorities.

Mr. Leissner said he wasn’t proud of his untruths, and had lied to the F.B.I. after his arrest because he was scared. Finally, though, he had “come clean,” he said.

As part of his plea deal, Mr. Leissner agreed to forfeit $44 million and shares in a company worth hundreds of millions more. He has avoided spending any time in jail as a result of his cooperation. (Mr. Ng spent six months in a Malaysian jail before he was extradited to the United States in 2019.)

Mr. Leissner’s cooperation helped prosecutors leverage a guilty plea out of Goldman, a typical prosecution strategy of striking a deal with a white-collar defendant to land a proverbial bigger fish. But it’s unusual for Mr. Leissner to be testifying against someone he once supervised.

“In a case like this, you hope to avoid a situation where you have a cooperator testifying against someone who is a subordinate,” Ms. Roiphe said.

Some lawyers speculated that federal prosecutors never expected they would have to put Mr. Leissner on the stand. Instead, they may have been banking on a guilty plea by Mr. Ng before a trial, keeping much of Mr. Leissner’s dirty laundry under wraps.

Mr. Ng’s trial is scheduled to go on for at least two more weeks, and it’s hard to know just how Mr. Leissner’s testimony will factor in the jury’s deliberations. The government is calling other witnesses to testify about how both men violated Goldman rules in seeking the lucrative bond underwriting business, and to review bank records for Mr. Ng and his wife.

Even if the jury trusts Mr. Leissner’s testimony, the litigation may not be over.

The trial had to be paused for several days to allow Mr. Ng’s lawyers time to review tens of thousands of emails and other private documents belonging to Mr. Leissner that the prosecution did not deliver until after the trial began. Prosecutors called the delay “inexcusable.”

Mr. Agnifilo has said the government’s failure to produce the documents in a timely fashion impeded his ability to prepare for the trial. Legal experts have said the issue could give Mr. Ng grounds for an appeal if convicted.

“It is inexcusable and messy work,” Ms. Roiphe said. “There is an obligation to get this right, especially when you have a big, high-profile case.”

Top Stories: NY Arbitrator and Mediator Marc J. Goldstein exposed by whistleblower in alleged Goldman Sachs bribery scheme.